According to Hindus the river Ganga is sacred and a feminine river. The river is worshiped by Hindus and personified as a Devi goddess, who holds a significant place in the Hindu religion. Hindu faith holds that bathing in the river, especially on certain occasion causes the forgiveness of sins and helps to attain salvation.

A high court in India last week accorded the Ganges and Yamuna—two of India’s holiest rivers—the status of living entities, granting them the same legal rights as people, in a push to protect the waterways from further damage from pollution.

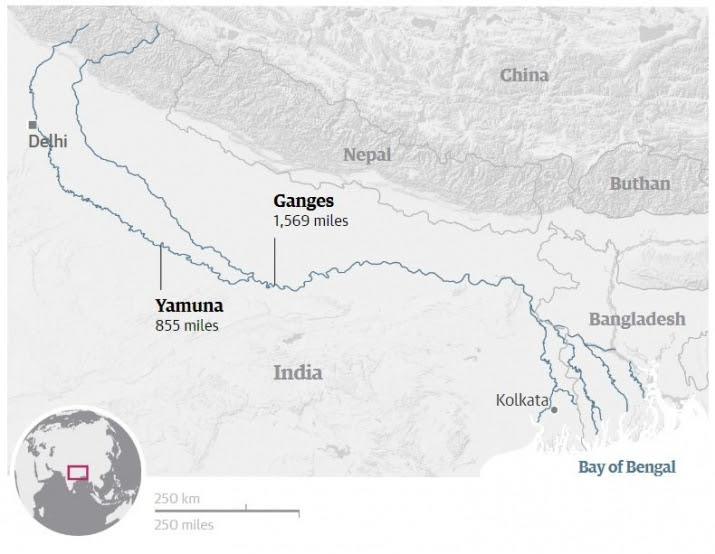

Judges Alok Singh and Rajeev Sharma of the high court of Uttarakhand, a northern state in India (where the Ganges originates), declared the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, and their tributaries, “legal and living entities having the status of a legal person with all corresponding rights, duties, and liabilities.” The rivers are the first non-human entities in India to have been granted this status. (The Guardian)

Environmentalists have applauded the ruling, which effectively gives the rivers the right to protection, and equates pollution, and thereby harming the river, to harming a person. The court officials stated that the decision would aid the “preservation and conservation” of both rivers.

The rivers are considered holy and are seen as goddesses by India’s Hindu majority. The Ganges, specifically, is attributed healing powers and is used for ritual bathing and the scattering of funereal ashes. The Yamuna is considered somewhat of a twin of the Ganges; the two rivers run roughly parallel until they merge. The court ruling described how Hindus feel that they “collectively connect with [the rivers]” and added: “The rivers are central to the existence of half of the Indian population and their health and well being. They have provided both physical and spiritual sustenance to all of us from time immemorial.” (BBC)

Despite their importance to a large part of the Indian population, the rivers are heavily polluted as they are used as a drain for industrial waste and untreated sewage from cities. In some parts of the Yamuna, for example, water quality has deteriorated to the extent that it no longer supports life, while further along its stream, the water is treated chemically to supply 19 million residents in New Delhi with drinking water. Rapid urbanization and industrialization continue to threaten both rivers, making the unusual ruling a necessity as they are on the verge of “losing their very existence.” (Deutsche Welle)

The court has appointed thee officials to act as legal custodians of the rivers, who will oversee their protection and conservation. In addition, a management board should be established within three months following the ruling.

The case was brought to court after complaints that the governments of Uttarakhand and the neighboring state of Uttar Pradesh were not cooperating with the federal government efforts to protect the Ganges.

The judges drew inspiration from a similar ruling two weeks ago in New Zealand, which made the Whanganui River, in New Zealand’s North Island, the first river in the world to be granted the status of a legal person. This ruling was the result of a 140-year-long battle of the local Māori iwi (tribe) to have the state recognize the river as their ancestor. As the lead negotiator for the iwi noted: “We have fought to find an approximation in law so that all others can understand that . . . treating the river as a living entity is the correct way to approach it . . . instead of the traditional model for the last 100 years of treating it from a perspective of ownership and management.” (BBC)

Environmental activists are hopeful that India’s ruling will provide a new incentive for the country to clean up its rivers. Himanshu Thakkar, coordinator of South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers & People, takes a more pragmatic approach: “There are already 1.5 billion liters of untreated sewage entering the [the Ganges] river each day, and 500 million liters of industrial waste[.] All of this will become illegal with immediate effect, but you can’t stop the discharge immediately. So how this decision pans out in terms of practical reality is very unclear,” he said. “[The] government has been trying to clean up the river by spending a lot of money, putting in a lot of infrastructure and technology, but they aren’t looking at the governance of the river. . . . You need a simple management system for each of the [sewage treatment] plants and give independent people the mandate to inspect them, question the officials, and have them write daily and quarterly reports so that lessons are actually learned.” (The Guardian)

Indian Mythology states that Ganga is the daughter of Himavan – the king of the Mountains She had the power to purify anything that touched her. According to myths Ganga flowed from the heavens and purified the people of India. After the funeral, Indians often submerge the bodies of their dead in the Ganga, which is thought to purify them of their sins.