By Shyamal Sinha

Two Japanese monastics, a monk and a nun, however have taken an alternative approach by promoting Buddhism through modern music: the monk, Kanho Yakushiji, and the nun, Satoshi Yamamoto, combine Buddhist sutras with modern musical arrangements and technology.

Yakushijii and Yamamato formed the band Kissaquo in 2003, and since then have been performing their music in temples and small clubs. Their songs have particularly attracted young people to Buddhism, and since forming the band, the pair has released several albums, which are available on online music sharing platforms. Among their most popular releases, the Heart Sutra, one of the best known discourses in Mahayana Buddhism, has been a hit. (Nikkei Asian Review)

Although originally from a monastic family, Yakushiji was reluctant to follow in his father’s footsteps as a Zen monk. “I didn’t want to be a monk,” Yakushiji told Japanese public broadcaster NHK. “I was struggling to find something else, and found music.” After releasing some albums, he was not happy with his growing fame and instead turned back to monastic training to become a full-fledged monk. During his two-year training, Yakushiji realized the Heart Sutra was special: “To me, the Heart Sutrarepresents human connection,” he explained. “We exist because other people are connected to us.” (NHK)

However, the singing monk realized that the Heart Sutra was difficult for many people to understand. As an experiment, Yakushiji combined the sutra with music to make it more accessible to the public. After a fan shared the track online, it reportedly received nearly 2 million hits and numerous comments, convincing organizers of a Chinese music festival to invite him to perform in China. “The audience created a very warm atmosphere . . . I enjoyed it very much,” Yakushiji said of his performance. (NHK)

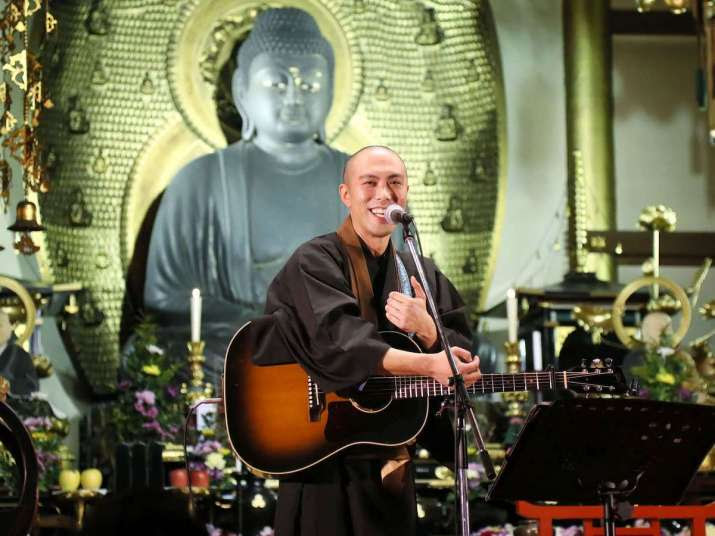

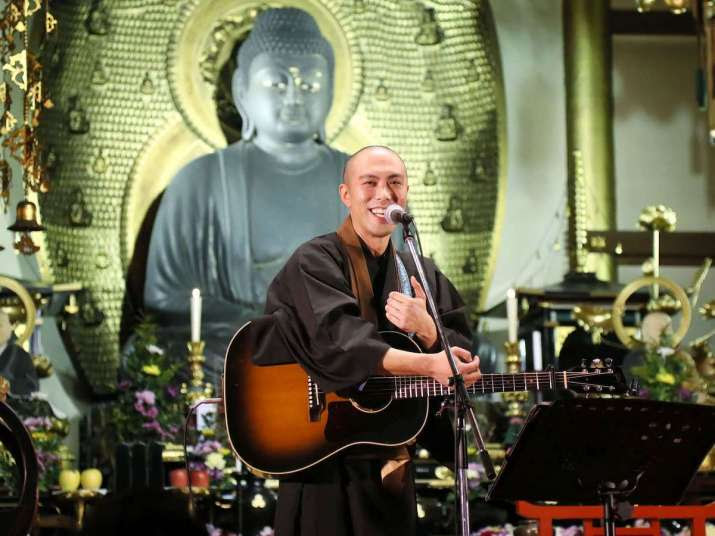

Along with Yamamato, Yakushiji performed at Seigan-ji, a temple in central Kyoto, in June 2017. The pair sang 14 songs in a two-hour concert, with Yakushiji engaging with the audience between songs. “I used to have fuller hair,” the monk joked about his shaven head. “The priest outfit is comfortable to play guitar in, except that it’s hot!”

At the end of the show, Kissaquo fan Itaru Sanno observed that it had been his first time to see a live music performance at a temple, and that the show had given him a more positive view of Buddhist temples: “It shattered my image of temples as gloomy places.” Also in the audience that day was 57-year-old Sayuri Somatori, who expressed enthusiastic support and affection for the monastic singers. “It’s just like love for a son,” she said. (Nikkei Asian Review)

Yakushiji explained that temple halls, with their high ceilings, offered excellent acoustics for musical performances. Coupled with that, he said, audience members sit on zabuton cushions, enhancing the feeling that they’re attending an event at a temple, helping to create a calm and reverent ambiance in which they can also engage with fellow music lovers. “I want people to enjoy meeting those they would not otherwise know,” he added. (Nikkei Asian Review)

Another singing nun, performing under the stage name Idol-bosatsu, is on a similar mission to attract young people to Buddhism, singing techno-pop tunes crafted by professional songwriters. As a little girl, Idol-bosatsu dreamed of being a pop star, and with the support of her father, also the chief priest of a temple, she was able to draw young audiences to the temple. After achieving her initial goal of garnering public attention, Idol-bosatsu expressed a desire to have a proper Buddhist stage name. “I want to strive to do good as my real self from now on,” she told the Nikkei Asian review in 2017, adding that, thanks to her concerts, more young people had begun visiting her temple to discuss Buddhism and their everyday worries. (Nikkei Asian Review)

Reverend Tadato Wakabayashi, a priest who publishes a Buddhist magazine, praised the concerts as a valid way of encouraging more interest in Buddhism. He welcomed the musical initiatives of the young monastics performers, saying, “I hope the efforts of younger priests can help people feel closer to Buddhism.”