By Shyamal Sinha

Mongolians believed in shamanism in ancient times. Traditional Mongols worshipped heaven (the “clear blue sky”) and their ancestors, and they followed ancient northern Asian practices of shamanism, in which human intermediaries went into trance and spoke to and for some of the numberless infinities of spirits responsible for human luck or misfortune. Buddhism was introduced from Tibet to Mongolia in the beginning of the 13th century, when the red hat sect of Tibetan Buddhism began to find its followers among the Mongolian rulers. In the 16th century, many feudal lords as well as herdsmen shifted to the yellow hat sect of the Dalai Lama. In the second half of the 16th century it became the state religion of the Mongol Princes. The Mongols have used Tibetan Buddhism as way of unifying Mongolians and creating a sense of nationalism. It has incorporated many shamanist symbols and rites.

In the wake of decades of suppression under Communists rule, Mongolia is beginning to reconnect with its spiritual roots, and a new generation of monastic practitioners is reviving he country’s centuries-old Buddhist heritage. However, the young monastic flag-bearers face numerous challenges and an uncertain future as the Dharma flowers anew.

The Mongolian People’s Republic was declared a Soviet satellite state in 1924, and for much of the turbulent 20th century, Mongolia’s communist government suppressed religious practices in the country. In the late 1930s, the regime shut down almost all Buddhist monasteries and killed tens of thousands of people, including an estimated 18,000 monastics. More than 1,250 monasteries and temples were demolished and countless religious artifacts lost, while the number of Buddhist monks in Mongolia declined from some 100,000 in 1924 to 110 by 1990.

“After 60 years of oppression, [Mongolia’s] monkhood was pretty much destroyed,” noted Canadian Tibetologist Glenn Mullin. (The Nation)

Following the fall of communism in 1991, Vajrayana Buddhism, which had been the country’s predominant religion, has again risen to become the most widely practiced spiritual tradition.

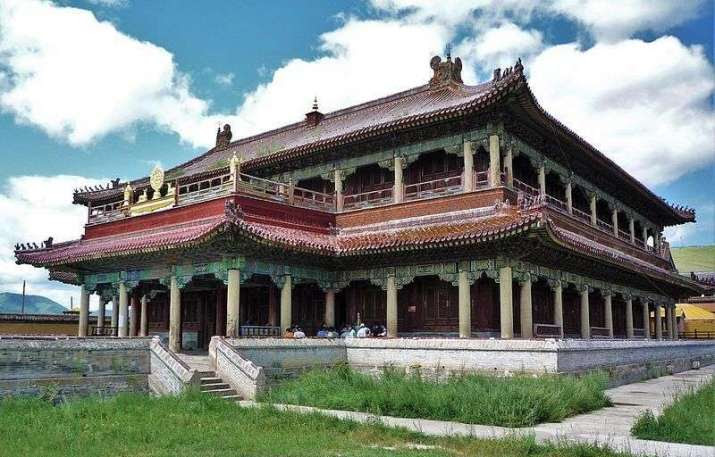

Nestled in the steppes of northern Mongolia, Amarbayasgalant Monastery is a monument to the country’s contemporary Buddhist revival. One of the three largest Buddhist monastic centers in Mongolia, Amarbayasgalant dates to the 18th century and was one of the few monasteries to survive the anti-religion purge during the 1930s, when the communist regime executed many of the monastic residents and looted most of its relics, artifacts, and manuscripts.

Of the more than 40 temples that originally made up the monastic complex, only 28 remain, which underwent UNESCO-funded restoration from 1988. The complex that housed as many as 3,000 monks at its peak is now home to fewer than 40, the oldest of whom is the monastery’s 35-year-old abbot.

At just 29 years of age and with only four years of monastic study under his belt, senior monk Lobsang Tayang has been charged with mentoring two younger monks, aged 10 and 11—a role he would normally only qualified to attain after some 20 years of study. “I felt like I hadn’t gained enough knowledge yet,” said Lobsang. “I was thinking, ‘Is it right for others to call me teacher when I myself am still learning?’” (Reuters)

The younger monks study and memorize Buddhist scriptures during the morning, and in the afternoon turn to subjects such as literature and mathematics. One of the difficulties for modern Mongolia’s Buddhist resurgence is finding young people willing to accept the monastic life and pursue it over the long term.

Badamkhand Dambii, the mother of 11-year-old novice Temuulen, recalls her son’s trepidation when she first proposed sending him to the monastery. “He didn’t like the idea because he was afraid of the paintings and altars of the deity,” she related. “He said they were frightening.” (Reuters)

While the roots of Buddhism in Mongolia are slowly strengthening, the reaities of monastic life pale in comparison to the lure of the outside world for some of the monastery’s young residents, who are only permitted to spend two weeks of the year outside its walls. And while Amarbayasgalant does have limited Internet access, smartphones are only permitted for monks aged over 25.

“Nowadays it’s very rare to find monks who can remain faithful to their vows,” Lobsang lamented. (Reuters)

Heavily in debt, the country’s government has difficulty providing the limited infrastructure needed for Buddhism to fully flourish in Mongolia and many monasteries lack proper residential amenities for the country’s estimated 3,500 monks. These numbers are expected to increase as the first wave of young monastics sent to be educated in India, Nepal, and Tibet return to their homeland to face some challenging secular realities.

“It’s easy to chop down a forest, right?” observed Lobsang Rabten, Amarbayasgalant’s second-most senior monk, who hopes to see the monastery restored to its former glory. “But it takes a long time for new trees to grow back.” (Reuters)

According to data from Mongolia’s 2010 national census, 53 per cent of Mongolians identify as Buddhists—mainly expressions of the Gelug and Kagyu lineages of Vajrayana Buddhism. Muslims represent 3 per cent of the population, the Mongol shamanic tradition 2.9 per cent, Christians 2.1 per cent, other religions 0.4 per cent, while 38.6 per cent profess no religious affiliation.