On May 7, the new exhibit “Cave Temples of Dunhuang” at the Getty Center in Los Angeles will display artworks and replicas of three caves, selected from hundreds hewed out of cliffs from the fourth to the 14th centuries near Dunhuang, a city more than 1,200 miles west of Beijing at the edge of the Gobi Desert.

Merchants and other travelers created the caves as safe places to rest and meditate along a trade route skirting the desert, part of an ancient network that linked China with Mediterranean and Indian civilizations. Over the centuries, artisans added their own handiwork, leaving behind images and inscriptions that experts can now date by the styles of dress they depict. The exhibit includes objects that Buddhists used for prayer and meditation and to gain karmic merit.

Thanks to the dry weather, an uncanny amount of artwork remains intact. Foreign explorers visited the caves in the early 1900s and sent many objects to European, Indian, Japanese and American collections. Many works in the Getty exhibition are on loan from museums in Europe. Despite the exports overseas, thousands of silk and paper manuscripts remained within the walls of the caves.

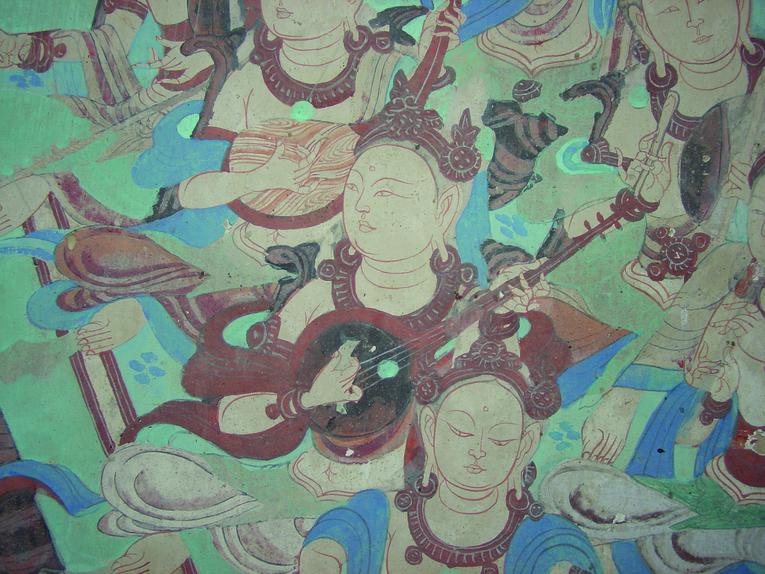

The Chinese government finally opened the caves to the public in 1980. For more than 25 years, the Getty and the Dunhuang Research Academy, devoted to the caves’ upkeep, have collaborated to preserve their contents. Under high ceilings—some over 40 feet—colorful murals illustrate Buddhist sermons and stories. Among the objects in the show is a wood block print displaying an important Buddhist sermon, the Diamond Sutra, aimed at dispelling the illusory nature of the material world.

— Co-curator Marcia Reed thinks that the exhibition, which ends Sept. 4, will find a ready audience in California, where she sees new interest in meditation and Buddhism.

Since the 1950s, artists from the Dunhuang Research Academy have created replica caves, painting on huge pieces of paper. In this exhibit, the replicas were mounted on wooden supports and erected at the Getty’s entrance.

At the desert site, the Getty has helped researchers use fences and screens to protect the caves, which once were considered great displays of wealth. Ms. Reed loosely compares them to Beverly Hills mansions or Medici palaces in Italy. “It is Buddhist glamour,” she jokes.