Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center (TBRC) is a 501(c) non-profit organization dedicated to seeking out, preserving, organizing, and disseminating Tibetan Buddhist texts and Tibetan literature. Founded in 1999 by E. Gene Smith, TBRC is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts and hosts a digital library of the largest collection of digitized Tibetan texts in the world.

TBRC’s Harvard Square headquarters facilitates its ongoing cooperative relationships with Harvard University. TBRC also has international offices in New Delhi, India and Kathmandu, Nepal, and a newly opened scanning and text-preservation center located within the E. Gene Smith Library at Southwest University for Nationalities in Chengdu, China.

In 1999 with friends including Harvard professor and fellow Tibetologist Leonard van der Kuijp, he founded the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Smith’s texts from India that were digitized at TBRC became the foundation for Tibetan studies in the United States.

Marking its ambitious initiative to expand the scope of its mission to digitally preserve the literary traditions of Tibetan Buddhism to encompass Buddhist traditions in other languages,* the former Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center has announced that it has officially changed its name to the Buddhist Digital Resource Center (BDRC). Established with the objective of preserving, cataloguing, digitizing, and disseminating Tibetan Buddhist literature, the BDRC will this year begin digitally preserving and making accessible Buddhist texts and traditions in other languages, including Chinese, Pali, and Sanskrit.

“This initiative will be the first in history to unify the diverse array of Buddhist texts into a single, all-encompassing digital resource for the core textual sources of Buddhism,” The Cambridge, Massachusetts-headquartered BDRC announced. “This has never been attempted, has never been done, and has never before been possible. We are thrilled to now be applying our successes preserving and making accessible Tibetan materials to the vast array of other language collections urgently in need of support.” (Buddhist Digital Resource Center)

Leveraging the transformative power of digital technology, the BDRC has created an unparalleled digital library and Buddhist resource that is accessed on a daily basis by thousands around the world, in the process transforming the inquiry into Buddhism’s textual heritage. The BDRC’s expanded reach will focus on textual sources from Central, East, and Southeast Asia, which are particularly at risk of being lost in this era of socio-economic, political, and environmental instability.

“Basically, we’ve been working for 17 years in the Tibetan text preservation space. In 2015, our board looked at the possibilities and potentials and decided that we would move beyond Tibetan and work in other languages,” BDRC executive director Jeffrey Wallman told Buddhistdoor in Hong Kong. “While we have the core capacity to [handle the broader scope of work], we have to expand the human capacity in certain areas. So, for example, we’ve started a project in Bangkok scanning Burmese and Thai manuscripts—including Burmese-language manuscripts, Thai-language manuscripts, Burmese Pali manuscripts, and Thai Pali manuscripts.”

Since its establishment in 1999 by E. Gene Smith (1936–2010), a student of Tibetan Buddhism, literature, and history, the BDRC has built an online library that today ranks as the most extensive single collection of Tibetan literature in the world. The project’s goal of digitally preserving the literature and culture of the Tibetan people has already had a profound impact on the future of Buddhism that has far exceeded the scope of its founding. Much of this work has been carried out with the support of the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation, the Gruber Foundation, and the Khyentse Foundation, a non-profit organization founded by Bhutanese lama Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche.

Digital Resource Center

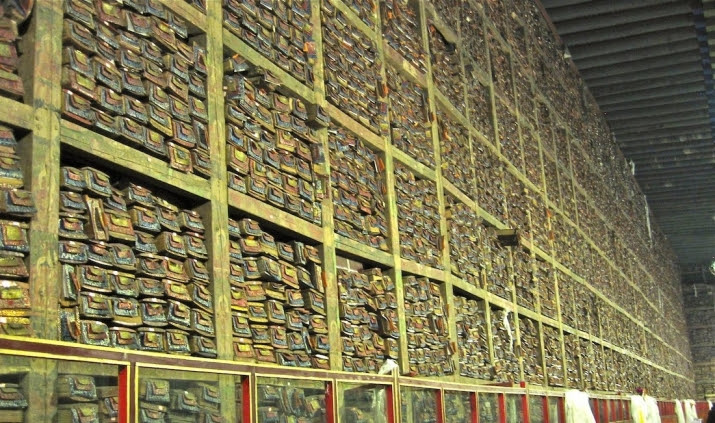

“We spend a lot of energy digitizing multiple editions of manuscripts, and carefully cataloguing and identifying what texts they are, where they come from, and so on. We started in 1999 with our Tibetan program and we’ve done about 13 million pages,” said Wallman. “It’s a kind of cultural memory and heritage preservation because these works are very significant, and as Buddhism moves into new languages—in the US and the West, and even as it migrates throughout Asia—having access to the source texts to validate translations is a very stabilizing factor.

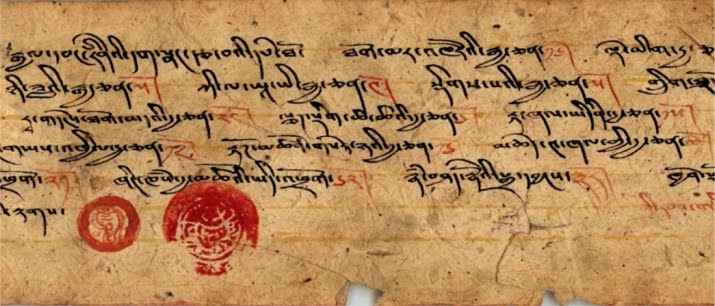

“We scan everything we can, so you can see the migration of terminology, local dialects, local variations, to the extent that it’s written down in texts. That’s why we scan more than just the canonical versions of texts . . . we scan whole traditions and we want to the same for Pali, for Sanskrit, even for Chinese Buddhism.”

The project has resulted in an invaluable collection of digital texts that span more than 1,300 years and includes philosophical and religious treatises, biographies, as well as works on alchemy, art, astrology, astronomy, folk culture, geography, grammar, history, poetry, and traditional medicine.

“Now, many of these other languages already have a lot of people working on digitizing projects—in Chinese, for instance—so the texts are not as vulnerable, necessarily. In those cases, we will also catalogue material that other people have and use our cataloguing system to point to existing digital collections. So the scope of our work for each language, each tradition, is different,” Wallman explained.

“There are teachers all over the world who’ve been able to download these texts, and give teachings from these texts,” he noted. “And as a result, we’ve seen some interesting cultural preservation activities—some communities have taken the digital scans and carved woodblocks from the scans and started printing block prints, so a revival of print culture is taking place, which is really great.”

Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center (TBRC) to Buddhist Digital Resource Center (BDRC). In 2017, BDRC will begin preserving and making accessible texts in languages beyond Tibetan, starting with Pali, Sanskrit, and Chinese.