By Shyamal Sinha

The word Swastika, स्वस्तिक, is made from Sanskrit words su + asti = well + being (सु + अस्ति = स्वस्ति) or all be well. , it a symbol, i.e. swastika is one that symbolizes well being, brings well being, good fortune.

Next to OM ॐ, swastika is the most ubiquitous and revered symbol in one of the oldest living tradition of India.

The swastika (Chinese: wan; Japanese: ban) is a geometrical figure and ancient religious icon that has been used throughout Eurasia since antiquity. It is particularly prominent in the Dharmic traditions of India, and subsequently appears throughout East Asia as well. However, due to Nazi Germany’s appropriation of the swastika and the reprehensible violence perpetuated in its name, portraying a swastika in its historically sacred, pan-Asian context is taboo throughout the West.

New York City-based Rev. Kenjitsu Nakagaki, a Japanese Buddhist priest who encountered this taboo for himself when he first moved to the West (Seattle) in 1986 (he was berated for arranging chrysanthemums in the shape of a Buddhist swastika), is reaching out to provide an account of the legitimate use of the controversial symbol in the Buddhist context. In 2012, the 57-year-old reverend completed a dissertation that would form the basis for his recent, self-published book The Buddhist Swastika and Hitler’s Cross(2017), which “details the swastika’s Sanskrit origins, then delves into its use in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, predating by centuries Hitler’s Nazi propagation of the symbol.” (JapanToday) Indeed, the Buddhist swastika and the Nazi appropriation of the archetype have distinct differences. The Buddhist version stands flat, with left-turning arms, while he Nazi swastika is right-turning on a 45-degree angle. Stone Bridge Press republished Nakagaki’s book this year.

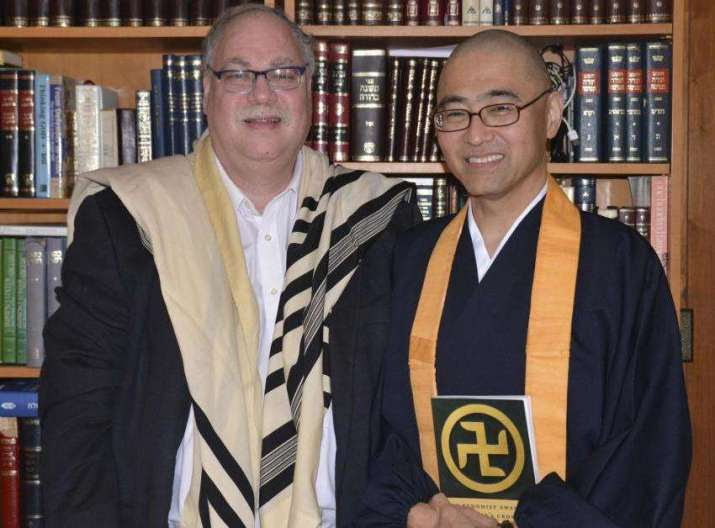

Last month, Nakagaki participated in an interfaith discussion with Rabbi Alan Brill, chair of Jewish Christian Studies at Seton Hall University in New Jersey. Who, their discussion, said: “The word is misused entirely but that is now the English word for all those designs. In the end, it is still being used as a hate symbol in America. It is not a historic symbol, it is something being used right now.” (JapanToday)

Rabbi Abraham Cooper, associate dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center (which combats anti-Semitism), told JapanToday that while the dark past of the Nazi swastika should never be forgotten (and was constantly reused by extremist groups and individuals today), Nakagaki’s efforts were important. “Every effort to educate people on both sides, in Asia and elsewhere around the world, is a positive thing.” (JapanToday)

Earlier this year, reports circulated on the Internet about Japanese schoolgirls reclaiming the swastika through selfies and other photos on social media like Line, as the symbol also means “good fortune” in Japan. The Japanese word for the symbol, manji, has been used in a variety of other contexts, including the Japanese equivalent of saying “Cheese” before a photo is taken, describing a person with a playful or cheeky personality, or using it as a pun on the word maji, translated as “really?.” This is perhaps easier done in Japanese as the Nazi swastika has its own word to distinguish it from the manji: the haakenkuroitsu, from the German hakenkreuz.

The effort to reclaim the swastika could perhaps be seen as part of a wider Japanese Buddhist effort to shift negative narratives and perceptions about Buddhism in the country, including how it is sometimes, perhaps unfairly, seen as apathetic to contemporary social concerns or focused only on holding religious rituals or maintaining landed property via its ancient temples. Not a few spiritual leaders have found theologically productive ways to address the needs of its congregants, including Kokujo-ji’s Shingon fire ritual to purge online hatred, Daizen-ji’s Ven. Nemoto’s suicide prevention workshops with people who have social withdrawal symptoms (hikikomori), or in the case of Ven. Fujioka of Vowz Buddhist Bar, doing outreach for people who have lost faith in religion and life.

“This narrow and limited perspective [of the Nazi swastika] is unacceptable for those of us who value and have grown up with the swastika in our religions and culture,” said Nakagaki, whose efforts seem to be paying off in gradual but important ways—particularly by reassuring people that things like the appearance of the Buddhist swastika denoting Buddhist temples on tourist maps for visitors to Japan are innocent and an example of how this sacred icon was supposed to be deployed. (JapanToday)

An auspicious symbol in Indian household.