By Shyamal Sinha,New Delhi

The ruins of Bazira, also called Vajirasthana, are near the modern town of Barikot, where the Italian Archaeological Mission has been excavating since 1978. Over the years archaeologists have excavated the ancient city to reveal palatial quarters and shrines. Bazira is an important center for the study of Greco-Buddhist art.

Excavations of the ruins of the ancient city of Bazira in Pakistan’s Swat Valley have recently revealed a shrine and courtyard, where archaeologists have unearthed sculptures and carvings that date back more than 1,700 years and depict stories from Buddhism and other ancient religions.

Also known as Vajirasthana, Bazira was established as a small town in the 2nd century BCE, eventually growing into a city as part of the Kushan empire (30–375). During the 3rd century, the city was devastated by a series of earthquakes and gradually fell into ruin. Today, the remains of Bazira can be found near the village of Barikot at the southern end of the Swat Valley. The Italian Archaeological Mission in Pakistan has been excavating the ruins since 1978, in the process unearthing sculptures and carvings that provide insights into the religious lives of the city’s inhabitants, who followed a number of ancient religions, including Buddhism.

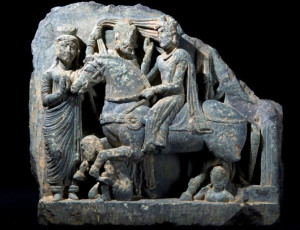

One of the relics discovered at the shrine, a carving 13 inches wide and 11 inches high, illustrates the departure of the young Prince Siddhartha Gautama from his palatial home on his horse Kanthaka. Prince Siddhartha is believed to have grown up in a palace in Kapilavastu, the ancient capital of the Shakya kingdom, in present-day Nepal, until he decided to give up his privileged life to gain a greater understanding of the world and to seek enlightenment.

In describing the sculpture for The Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology, Luca Olivieri, the director of the excavation at Bazira, said that the figure depicted wearing a crown and holding her hands in veneration before Prince Siddhartha was the town goddess of Kapilavastu, while those supporting Kanthaka’s hooves below were spirits known as yakshas. Behind them is the figure of a man—possibly a deity—with his left hand held to his mouth and his right hand waving a scarf-like garment called an uttariya.

Another carving found at the site depicts a stupa flanked by two columns with lions on top. According to Olivieri, the scene could be a representation of a real stupa that once existed in the Swat Valley. “Real stupas with four columns—topped by crouching lions’ statues [sic]—at the corners of the lower podium have been documented in Swat,” Olivieri told Live Science. In the 1960s and ’70s, archaeologists excavated a similar stupa that is believed to have been in use between the 1st and 4th centuries.

A third carving unearthed in the courtyard has been dated to a time after the shrine was damaged in an earthquake. Olivieri described the relic as depicting “an unknown deity, an aged male figure sitting on a throne, with long, curled hair, holding a wine goblet and a severed goat head in his hands.” He noted that the figure resembled images of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, fertility, theater, and religious ecstasy.It seems that Buddhist schools tried their best to curb the habit of consuming wine and other ‘intoxicating drinks’ even amongst the monastic community,”

Olivieri said the goat’s head in the carving represented a local passion: “The goat is an animal associated to the mountains in the cultures of [the] Hindu Kush, the local region,” he observed, adding that it was used as an icon in ancient rock art. (Live Science)

The archaeologist noted that viniculture and winemaking had been widespread in the Swat Valley to the degree that alcohol consumption had become a problem. “It seems that Buddhist schools tried their best to curb the habit of consuming wine and other ‘intoxicating drinks,’ even amongst the monastic community,” he said. (Live Science)